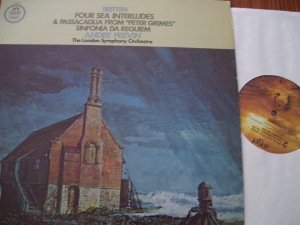

I was introduced to the Britten Peter Grimes Interludes by my uncle, a classical LP collector who unfortunately tossed his entire collection of early stereo LPs when going through a divorce years ago. I can’t remember, for the life of me, the performance he first sent me on cassette tape. I wound up learning to love the four-movement suite, despite an inability to ever connect with Britten overall, in his operatic works or otherwise. In this short ensemble however he grabs you and holds on tight.

I was sparked to revisit my preferences in this piece recently when uncovering a Van Beinum Concertgebouw mono LP, LL-917, the old red/gold FFRR label. Available on CD here, thought I can’t vouch for its sound quality. After a round on the VPI, I was shocked at the vivid sound and subtle performance of my old, round piece of plastic. I’d though one would only get this kind of trascendent performance from an English countrymen in such a work as this. But depsite the ticks and pops this is one remarkable reading. The orchestral depth is clear and arresting in both the attaca segments, and in the gentler ones.

I was sparked to revisit my preferences in this piece recently when uncovering a Van Beinum Concertgebouw mono LP, LL-917, the old red/gold FFRR label. Available on CD here, thought I can’t vouch for its sound quality. After a round on the VPI, I was shocked at the vivid sound and subtle performance of my old, round piece of plastic. I’d though one would only get this kind of trascendent performance from an English countrymen in such a work as this. But depsite the ticks and pops this is one remarkable reading. The orchestral depth is clear and arresting in both the attaca segments, and in the gentler ones.

The contenders I compared it with are Previn, on EMI/HMV 37142, unparalleled for sound in four-channel quadraphonic. Indeed this is one of the finest of all SQ quad records I’ve encountered — not ping-pong sonics with tubas coming from back left, but a full, rich sense of being in the middle of the orchestra. And when then full richness of “Moonlight” sinks over you, there is no other way to experience it. Van Beinum is skittish and edgy, vigorous, but even through the fog of years and technological development, cannot parallel Previn’s voluptuousness.

in four-channel quadraphonic. Indeed this is one of the finest of all SQ quad records I’ve encountered — not ping-pong sonics with tubas coming from back left, but a full, rich sense of being in the middle of the orchestra. And when then full richness of “Moonlight” sinks over you, there is no other way to experience it. Van Beinum is skittish and edgy, vigorous, but even through the fog of years and technological development, cannot parallel Previn’s voluptuousness.

And in the modern digital class I still recognize Handley, on Chandos 1184. Whatever my  uncle sent me on tape, this was my first CD of the piece, and it has not grown old. Compared to Previn (rich, measured, and voluptuous) and Van Beinum (edgy and energetic) Handley seems almost restrained, with that gorgeous Chandos sound, its vague reverb and even rhythms. How English! The opening bars are sprite-like, cascading and evoking an almost fantasy-like experience (nowhere more so than in those last few uneasy bars of the fourth movement). In this the Handley version is unique and delivers something entirely different from either Previn or Van Beinum.

uncle sent me on tape, this was my first CD of the piece, and it has not grown old. Compared to Previn (rich, measured, and voluptuous) and Van Beinum (edgy and energetic) Handley seems almost restrained, with that gorgeous Chandos sound, its vague reverb and even rhythms. How English! The opening bars are sprite-like, cascading and evoking an almost fantasy-like experience (nowhere more so than in those last few uneasy bars of the fourth movement). In this the Handley version is unique and delivers something entirely different from either Previn or Van Beinum.

There is a secret in these bars, and white maybe the most direct of these three interpreters, Handley’s hands manage the secret in most sensitive terms. Previn wraps us up in the secret, envelops us in it unabashedly. Van Beinum makes it a challenge to us. But Handley eases us in to the mystery. All three interpretations are revealing.

Together the trio present a full range of how these “Interludes” can be presented, painted in the most vivid and differentiated orchestral colors. Truly different interpretations of an underappreciated work.

P.S. Maybe Sir Simon will program this with Berlin. I would love to hear it, and I’m probably not alone.